Burnout Syndrome and its Prevention Within Your Team

“The land of burnout is not a place I would like to go back to” – Arianna Huffington

Now that burnout syndrome has officially been recognized as a disease by the World Health Organization (WHO), it makes sense to take another look at what exactly defines burnout syndrome and how people can contribute to its prevention.

The feeling of increased exhaustion and lack of motivation at work, especially in phases of increased workload, is not unknown to a large part of the working population. If the abovementioned phases occur more frequently, or even become a regularity at work, the associated symptoms also intensify, possibly leading to severe sleep disorders, depression, and possibly a nervous breakdown. The nervous breakdown is the culmination point of the burnout syndrome, which occurs more frequently in social professions (e.g. nursing, education, social work), but is by no means restricted to this occupational profile alone. Decisive factors for the onset of burnout are independent of one’s profession and can be traced back to circumstances such as inappropriate time pressure, unclear ideas about the job itself, but also unequal treatment or lack of communication at the workplace.

Burnout syndrome does not occur overnight, but rather develops over a period of 6 months to several years. Preventive action should be taken before first symptoms become apparent. Implementing these preventive measures is, of course, mainly the responsibility of each individual, but it also goes without saying that people in the immediate vicinity of the affected person, whether private or professional, can and should provide support during the process.

Among other things, managers can contribute a great deal to the receding of these symptoms or ensure that they do not occur at all. A high-quality, 3-part Gallup study by Ben Wigert and Sangeeta Agrawal on the subject called “Employee Burnout” elaborates on the reasons for burnout syndrome and how it can be prevented. First, however, it makes sense to take a look at the definition of the term itself.

Definition

In her book “Burnout: The Cost Of Caring”, the American psychologist and emeritus (Berkeley), Christina Maslach, defined the term and based it on the three main criteria of emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation and limited performance. A distanced and cynical attitude toward colleagues and work in general was observed in those affected, which led to general doubts about the personal success, suitability and meaningfulness of the work in question. Maslach’s term, which focuses on emotional exhaustion, has since been expanded to include further psychological and physical symptoms. This July, the World Health Organisation officially classified burnout syndrome as an independent disease. In the updated version of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD 11), the term is defined as a “feeling of burnout resulting from chronic stress at the workplace, which can lead to a negative attitude towards the job and lower performance, among other things”.

What to do?

According to the above Gallup study, managers are responsible for guaranteeing positive employee experiences and addressing stress factors at work. It is their duty to set clear expectations, remove barriers, facilitate collaboration and ensure that employees feel fully supported and are able give their best at work.

Are there concrete, actionable starting points? Absolutely.

1. Psychological Safety

Many of the problems listed above, such as an immense workload for individual employees, unclear distribution of roles, a lack of meaningfulness of work and the feeling of having no one to contact for help, can be reduced by creating a culture of psychological safety at the workplace. Psychological safety in this sense means that employees feel secure enough within their team to make themselves vulnerable, be it by introducing new, unconventional or perhaps even risky ideas or by addressing symptoms that could indicate an imminent burnout.

People working in a team in which they can’t make a mistake without attracting criticism, or where new, slightly unorthodox ideas are always smiled upon and waved off, will also be able to assume that their health complaints will fall on deaf ears, or even worse, will be regarded as a mental weakness, due to not being able to handle the pressure the job entails.

On the other hand, employees who are used to receiving constant, constructive feedback and are able to approach their colleagues and superiors without having to be scared of “putting themselves out there”, will not have such a great inhibitional threshold to ask for help if the workload becomes too intense. This employee won’t shy away from addressing problems with their boss, who may not even be aware of how much work has been assigned due to being overworked as well.

The implementation of psychological safety can take place in many ways and is a topic in itself. We have already elaborated further on this topic here, if you want to find out more. Additionally, we recommend the following German article, written by Herbert A. Meyer (HU Berlin), Mathias Wrba and Thomas Bachmann.

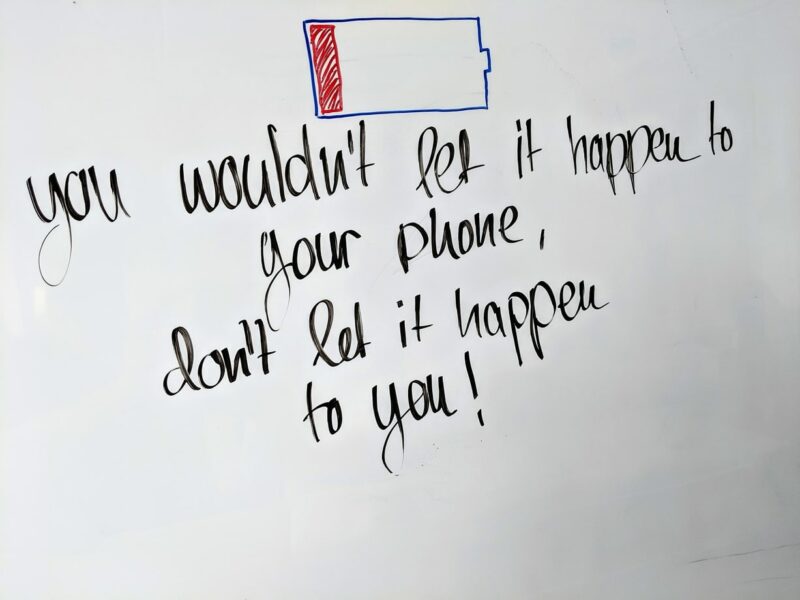

2. Real Leisure Time

“The wise rest at least as hard as they work.” ― Mokokoma Mokhonoana

Jen Fisher, Managing Director at Deloitte USA, wrote an article discussing practical suggestions for preventing burnout syndrome. Among other things, she highlights the importance of weekends and holidays. A study by Deloitte shows that almost 30% of the participants stated that they also work “many hours” on weekends. Less than half (43%) stated that they use their holidays completely. Even those who do, still check their emails or take calls instead of making a clean break from work. However, according to Fisher, this clean break is essential for recovery and should not only be allowed, but enforced by companies. Daimler has been radically implementing this principle for five years by simply deleting Emails addressed to employees on vacation. The sender is then informed that their mail has been deleted and has the option of contacting a colleague or resending when the employee returns to the office.

3. More Well-Being

According to the abovementioned Deloitte survey, 28% to 32% of participants said that flexible working hours, more holidays and/or in-house support programs would help reduce burnout. Other suggestions included office health and wellness programs as well as paid holidays for mental health or rest days. There are, however, alternative, more cost-efficient ways to increase well-being for companies that do not have a budget similar to Deloitte’s. Even in smaller companies, employee well-being measures can be implemented effectively and at low cost. As an example, our optional meditation course every morning only requires a smartphone and 13 minutes of our time. Our meeting room also functions as a common room with a foosball table and a Playstation for employees who want to relax or lose to Shin in Fifa.

As a manager you can introduce such measures yourself or at least regularly attend courses that increase company well-being. In a different Deloitte Study 31% of the respondents consider their direct superiors to have the greatest influence on their well-being at work. When employees see that even their boss invests some time to take part in a meditation or yoga course, they will feel more comfortable doing the same. However, if the direct supervisor labels the yoga course as a “waste of time” or “useless hippie fuss”, this not only demotivates the employees who feel like partaking or might actually need it, but also harms the above-mentioned psychological safety in the company.

In summary, the following points can be made: As a superior, make sure that your corporate culture places a very high value on psychological safety and, in your role model function, set the signal yourself that it is okay to take a breather from time to time and let personal issues take precedence over the professional.